Understanding Safety Culture: An Interview with Sociometri Founder Savannah Vlasman

Written by Joshua Hubbard

In safety-critical industries, understanding organizational culture isn’t a luxury, it’s a necessity. Few understand this better than Savannah, a behavioral scientist with academic roots at Harvard and Erasmus and nearly two decades of experience decoding organizational dynamics.

As the co-founder of Sociometri, she’s on a mission to make workplace safety smarter by making data-driven social science accessible. In this interview, Savannah unpacks the oft misunderstood concept of safety culture, explores its connection to human factors, and shares how Sociometri is helping organizations translate cultural data into real-world risk reduction.

Overview:

What is safety culture and why does it matter?

Connecting Human Factors and Safety Culture

How Sociometri measures safety culture

How Sociometri helps organizations proactively reduce risk

Closing Thoughts

What is safety culture and why does it matter?

“Organizational culture is the social context for members of the organization,” Savannah explains. “A strong culture increases stability and continuity — it makes people’s behavior more predictable. Safety culture, then, comprises the safety-relevant aspects of that broader culture.”

Yet, she notes, “There’s quite a bit of disagreement among researchers and disciplines about what dimensions a safety culture really includes — and don’t get me started on the battle of scope between safety culture and safety climate.”

Savannah points to several well-known safety culture definitions from the literature, each highlighting a slightly different angle. “Some define it as an objective measurement of attitudes and perceptions toward occupational safety. Other definitions focus not just on attitudes, but also on the social and technical practices that determine how safety is managed. It can be a complicated construct to measure. I would say safety culture is the collective perceptions, practices, values, and norms that are relevant to safe operations.”

Savannah’s approach to safety culture is from a sociological perspective. She emphasizes that culture isn’t about individual opinions but collective patterns:

“An individual is not our unit of analysis. Instead, we are looking for similarities across groups of individuals. However,” she adds, “organizational culture is aggregate. It’s made up of several distinct subcultural groups, often defined by similar roles, locations, or responsibilities. Capturing and analyzing subcultures can provide incredible insight into the cultural dynamics of the organization.”

Connecting Human Factors and Safety Culture

While safety culture represents the shared attitudes and behaviors that shape how an organization manages safety, it’s tightly linked to what’s happening at the individual level — the human factors.

“The term ‘human factors’ is more closely related to how an employee’s psychology and physiology are affected by environmental or situational conditions, things like fatigue, memory, stress, reaction time, and so on,” Savannah explains. “Safety culture, on the other hand, is about how the organization itself shapes those conditions.”

In other words, the two are connected but not identical. “If one person is stressed, we’re looking at human factors,” she says. “If everyone in the department is stressed, we’re likely looking at a systemic, cultural problem that needs to be addressed systemically.”

This is exactly why Sociometri brings both frameworks together. Sociometri has included human factor dimensions in its safety culture analysis.

By measuring individual-level human factors across an organization and then aggregating them, Sociometri identifies systemic patterns which reveal safety risks on an organizational level.

How Sociometri measures safety culture

“To make Sociometri, we had to be explicit about what [cultural] dimensions to include and how they are operationalized,” Savannah says. The team combined academic rigor with real-world practicality, integrating dimensions from exploratory studies on communication (Berends, 1996), teamwork (Brown & Holmes, 1986), training and knowledge (Coyle, Sleeman & Adams, 1995), and pressure (Glennon, 1982), and others, as well as incorporating constructs from applied frameworks like Just Culture and High Reliability Organizations (HRO).

“We wanted to capture a wide range of dimensions because a culture is incredibly multi-dimensional,” Savannah explains. “Just Culture and HRO are very practical, and we recognized the value of that. Sociometri synthesizes several validated and reliable questions from the leading research on safety culture, but we deliver the results through the lens of the Dirty Dozen, which are intuitive, easy-to-understand concepts that let safety managers hit the ground running.”

The outcome is a service that unites cutting-edge safety science theory, methodology, and analysis, translating them into a practical tool that helps organizations understand and manage risk.

How Sociometri helps organizations proactively reduce risk

“Safety culture is dynamic and responds to events both internal and external to the organization,” Savannah says. “Sometimes an internal event, an accident or mass-layoffs, may change the safety culture overnight.”

That’s why, according to Savannah, it’s important to regularly monitor safety culture.

“We measure, analyze, and monitor your safety culture continuously,” Savannah says. “By identifying irregularities and changes over time, we help organizations anticipate where problems might arise, before they cause harm.”

This approach allows Sociometri to alert clients to emerging risks that traditional audits or incident reports miss.

“Safety culture doesn’t determine safety outcomes,” Savannah emphasizes, “but it influences them. So, understanding your safety culture makes safety outcomes more predictable. And when you can predict accidents, you can prevent them.”

At its heart, Sociometri reflects Savannah’s belief that the foundation of safety management is listening to front-line workers.

“Employees are the experts; they know what’s up. Sociometri enables us to ask the right questions, capture and analyze their feedback, and use what we learn to reduce their risk of harm. We help organizations take better care of their people.”

Closing Thoughts

Sometimes safety is viewed synonymously with compliance, but Sociometri reframes it as a dynamic characteristic, grounded in data, guided by sociology, and powered by the voices of frontline workers.

By turning abstract cultural dynamics into tangible, measurable insights, Sociometri enables leaders to move from reactive to proactive safety management. It’s not just about preventing accidents; it’s about building systems that listen, learn, and adapt before harm ever occurs.

Want to learn more? Book a demo with our team.

—

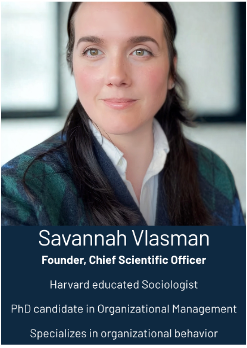

About Savannah Vlasman

Savannah Vlasman is the Founder and Chief Scientific Officer of Sociometri. A Harvard-educated sociologist and PhD candidate in Organizational Management at Erasmus University, she specializes in organizational behavior and safety culture.

Before founding Sociometri, she spent nearly two decades developing behavioral assessment tools to predict social and organizational outcomes, including identifying university students at risk of academic failure before they realized they were struggling.

About Joshua Hubbard

Joshua is an airline captain and business leader with a career that bridges aviation, operations, and strategy. At Sociometri, he advises on strategy, investment, and customer growth — supporting the global expansion of a platform that makes safety culture visible and actionable. With over a decade in safety-critical environments, he brings both cockpit experience and executive leadership to his advisory role .

Josh holds an EASA certification as Accountable Manager Flight Operations and Training and a safety certification for film and TV production, adding breadth to his understanding of risk and compliance across industries. As an Airbus captain, Joshua has first-hand experience leading crews where safety culture and decision-making directly shape outcomes.