Why Safety Culture Improvement Workshops Work

After learning How to find Safety Culture Improvement Projects using The DELTA System in our prior post, you might be wondering why a workshop is such a helpful tool in the process.

There are many reasons. Let’s get right into it.

Quantitative and Qualitative Data Fusion

As you now know, the D of the DELTA System stands for Data.

It represents the problem for which you are seeking solutions. We chose the word “data” instead of “area for improvement” or “problem” to emphasize that the area you wish to improve must be represented by an objective reference point—a baseline metric that can be reliably and repeatedly measured in the future.

Let’s talk about why a quantitative metric is so fundamental to continuous improvement.

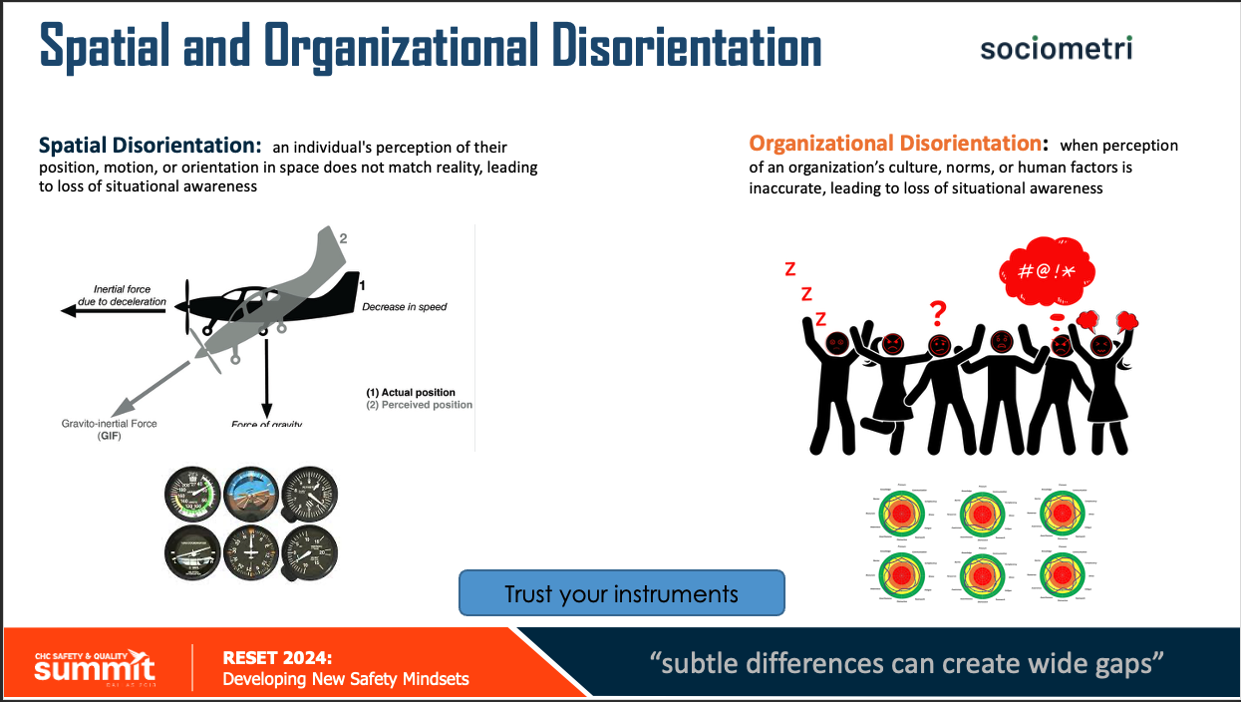

In aviation, pilots must be wary of a phenomenon called “spatial disorientation,” a condition where their perception of the airplane’s position does not align with reality.

This disorientation occurs when the brain misinterprets signals from the body, often due to a lack of visual references or conflicting sensory information.

Pilots may feel like they are flying straight when, in fact, they are unknowingly ascending, descending, or banking.1

The solution for this potentially fatal confusion has been drilled into pilots’ heads since flight school: trust your instruments.

This means a pilot should believe the readings on the aircraft’s instruments (the attitude indicator, altimeter, vertical speed indicator, etc.) over her own perception if she wants to understand the aircraft’s position in space.

Organizational Disorientation

Similarly, organizations can suffer from Organizational Disorientation – when the perception of the position and trajectory of the organization does not align with reality.

When the organization lacks clear, objective reference points for evaluating company culture, it is forced to fly blind, relying on a subjective “feeling” about how things are going.

Unfortunately, feelings do not always reflect reality, making it difficult to know whether the culture is flying straight and level or entering a nosedive.

The slide from our presentation at the 2023 CHC Safety Summit which introduced the concept of Organizational Disorientation.

The remedy for organizational disorientation is the same as spatial disorientation in aviation: trust your instruments.

In an organizational context, your instruments are not dials and gauges but instruments for gathering and analyzing quantitative data such as employee surveys, 360-degree feedback mechanisms, safety management system reports, and other performance metrics.

Just as pilots must sometimes disregard their instincts and instead rely on their instruments, so must leaders use objective reference points to ensure they are not off course.

Avoiding organizational disorientation hinges on systematically collecting and referencing quantitative data to ensure that decisions are aligned with the realities of the organization.

Sociometri’s Organizational Disorientation indicator. If you know, you know. :)

Quantitative Data

That is why selecting a reliable metric is the starting point of the DELTA System.

First, you need to know where you are.

Then, you must measure the same item again at regular intervals to gauge the effectiveness of your interventions.

In a stable organization, one can identify a change after two measurements and a trend after three measurements.

The direction of the trend line will tell you where you are headed and can act as an early warning system of trouble.

So, quantitative data is fundamental to systematic improvement and the DELTA System.

It is necessary, but is it sufficient?

What can we gain by gathering a group of employees together, asking their opinions, and learning about their perspectives?

Qualitative Data

There tends to be suspicion around perspectives and opinions.

Many of us, especially those from technical, scientific, or engineering backgrounds, trust quantitative data, not qualitative data. Put simply, we trust numbers, not words!

The skepticism toward qualitative methods makes sense. After all, the plural of anecdote isn’t data.

Wouldn’t it be foolish for an organization to make decisions based on what employees say? Some of them aren’t reliable enough to show up to work on time, let alone be a source of reliable data.

I’m reminded of the comedian George Carlin’s line,

“Think of how stupid the average person is and realize half of them are stupider than that.”

Qualitative data makes some people nervous.

It seems tidier to remove the human (a messy, unpredictable creature) from anything that needs to be reliable.

Yet, ask these same people how they feel about riding on an airplane with no pilot aboard, and many begin to feel a bit uncomfortable.

Even if an autopilot were capable of successfully piloting an aircraft from takeoff to landing, most passengers would prefer to have a human pilot around.

We want someone to validate that the computer is functioning properly; someone who is poised to take over if something goes wrong. We intuitively understand the benefit that comes from the fusion of technological precision and human intelligence.

The DELTA System incorporates both quantitative and qualitative methods because while quantitative data is necessary for controlling and monitoring, qualitative data is integral to understanding and improving.

Qualitative data is particularly critical when evaluating a human- centric system like an organization.

In organizational settings, quantitative data is often gathered through statistical methods that capture observable actions over time.

For example, studies on compliance with safety protocols often rely on direct observation or self-reported adherence rates.

Researchers might track the frequency of personal protective equipment use, record the number of safety incidents and near-misses, or log the time workers spend on specific tasks. However, without the context of qualitative insight, these metrics can be meaningless, or worse, misleading.

The British economist Charles Goodheart described this problem in his 1975 article on monetary policy.2 Goodhart’s Law states that when a measure becomes a target, it ceases to be a good measure.

Essentially, when organizations focus on specific quantitative metrics, employees tend to engage in practices that artificially inflate these metrics without genuinely improving the underlying processes or outcomes.

What happens when employees are told they must lower the number of incident reports? They don’t report incidents.

Goodhart’s Law: When a measure becomes a target, it ceases to be a good measure.

Quantitative and Qualitative Data Fusion

A data fusion of qualitative and quantitative data is necessary to avoid the warning given by Goodhart’s Law.

Contextualizing a metric is fundamental to improving it.

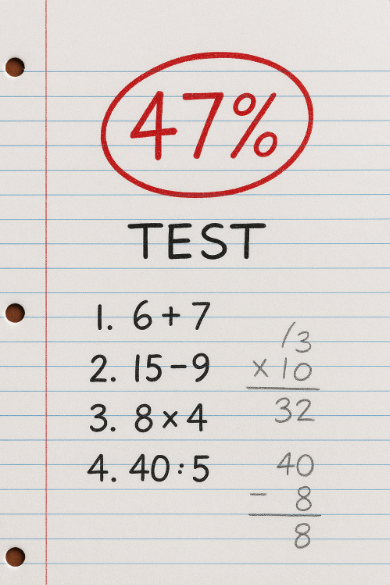

Here’s an example: Your middle schooler brings home a math test with a big red “47%” at the top.

This one wasn’t little Susie’s best work. :(

If you’re solely focused on improving the metric, you may give a speech like this: “I’m not happy; 47% is much too low. You need to get higher grades. I don’t want to see a score this low again. I expect you to score at least 80% on every math test from now on.”

Perhaps this speech will work, but it’s unlikely. What’s more likely is no improvement, or worse, hiding grades or cheating. It is insufficient to tell the child to improve the metric with no understanding of why the score is so low.

Does she not care about school? Or does she need tutoring? Or is she distracted, or does she have dyscalculia, or is she not getting enough sleep, or was she absent when the material was taught, or ...

Asking your child questions (collecting qualitative data) broadens the scope, deepens your understanding of the problem, and allows you to offer effective help.

The name we’ve given to this process of applying qualitative methods to quantitative metrics is interrogating the data.

The DELTA System interrogates the data with methods like thematic analysis and focus groups. The goal is to delve into the experiences and beliefs of individuals, contextualize the metrics, and reveal information critical for understanding.

These qualitative insights are vital because they uncover the deeply embedded beliefs that shape behavior.3

Without understanding the “why” behind actions, organizations risk responding to symptoms rather than causes, often allowing problems to persist beneath the surface.

Disregarding qualitative feedback, particularly from those on the front lines, means ignoring early warnings that could preempt larger problems.

Employing data fusion means the DELTA System can help us understand complex phenomena, identify the most promising interventions, and validate the efficacy of our interventions.

Local and Global Knowledge

The DELTA system includes a workshop as a mechanism for gathering local knowledge and transforming it into global knowledge.

Local knowledge consists of the practices, insight, and information held by individual employees at various departments and levels within an organization.

Global knowledge is complete information about the entire organization.

We commonly depict organizations as a hierarchy with senior leaders at the top. This is unhelpful to understanding the flow of knowledge in an organization because a hierarchy implicitly communicates that leadership has global knowledge.

Because leaders are depicted as having the entire organization under them, we mistakenly assume they should have all the knowledge they need to make good decisions.

However, no individual in an organization has global knowledge, not even leadership.4

Instead of a hierarchy, picture an organization as a constellation with local knowledge as its nodes. The organization exists relationally as the connections between those nodes.

The global knowledge of an organization comprises all the little nodes of local knowledge and the connections between them.

It is impossible to maintain both a detailed view of each node and the connections between them. As we zoom out to view the entire organization, we surrender detail.

Even when a leader’s purview is the entirety of an organization, he or she can still only achieve local knowledge.

A CEO’s local knowledge consists of the scope of his or her engagement with the organization. That scope is very broad, but not very detailed, and thus is always partial and imperfect.

This is why the DELTA System is based around a workshop.

We need to cast a wide net, pulling in as many nodes of local knowledge as possible, to achieve global knowledge.

Collectively, the workforce has all the knowledge necessary to inform quality decision-making.

Going to GENBA

A related concept is “genba,” a Japanese term for “the actual place.”

A principle of lean manufacturing, “going to genba” is the practice of visiting the factory floor to fully see and understand the realities of the front lines before trying to make improvements.5

If we want to find solutions that improve a reality, we need to include those who understand that reality in the process. This is why, when selecting workshop participants, we will ask you to select as broad a sample of the workforce as possible.

People Support What They Help Create

When employees are included in efforts to improve their organization, they become invested in the company’s success. People support what they help to create.

Participation in the DELTA Workshop turns participants into project champions who return to their departments as ambassadors eager to implement the solutions they helped to identify.

A workshop that involves a broad sample of the organization’s workforce is the best way to secure widespread buy-in.

Additionally, we encourage participants to discuss the topic of the workshop with coworkers before and during their participation.

Participants are then asked to introduce coworkers’ thoughts and ideas to the brainstorm, even if they do not agree.

This enables a broader collection of perspectives and encourages workshop nonparticipants to be involved in the process of improvement.

Culture-Shaping and Solution-Finding

Our philosophy is that sustainable, effective, continuous improvement is achieved via two complementary elements: solution-finding and culture-shaping.

The direct result of a DELTA Workshop is effective, realistic solutions: solution-finding.

The indirect result of a DELTA Workshop is the positive evolution of company culture: culture-shaping.

While solution-finding is necessary to address specific issues, shaping the culture ensures that those solutions are accepted, reinforced, and maintained by everyone in the organization.

You need both elements for continuous improvement: solution-finding for immediate issues and culture-shaping for sustained impact.

We will discuss in depth and reference each of these concepts in future posts. We will start with culture-shaping, a subtle yet crucial element of continuous improvement.

—

References

Federal Aviation Administration, Pilot’s Handbook of Aeronautical Knowledge (FAA-H-8083-25B), (US Department of Transportation, Federal Aviation Administration, 2016), https://www.faa.gov .

Charles A. E. Goodhart, “Problems of Monetary Management: The UK Experience,” in Papers in Monetary Economics, vol. 1 (Reserve Bank of Australia, 1975).

Ernest Nagel, “The Value-Oriented Bias of Social Inquiry,” in The Structure of Science: Problems in the Logic of Scientific Explanation (Harcourt, Brace & World, 1961), 484–97.

Etienne Wenger, Communities of Practice: Learning, Meaning, and Identity (Cambridge University Press, 1998).

Masaaki Imai, Gemba Kaizen: A Commonsense Approach to a Continuous Improvement Strategy (McGraw-Hill, 1997).